Today is Valentine’s Day, so I guess it’s appropriate to write a heart-related post.

What prompted it was a piece I saw on EE Times a week or so ago. In a post entitled “Implants Raise Security Awareness,” Joanne Emmett addressed the topic of medical device security. She started by going back a decade to the time when the doctors who were giving then-Vice President Dick Cheney a heart defibrillator replacement “ordered the device’s manufacturer to disable its wireless capacity.” There were concerned that the device could be hacked, and Cheney assassinated via technology. In a weird case of art imitating life, in an episode of the thriller Homeland, the serial number of the fictional VP’s pacemaker is stolen and a terrorist uses the information to rev up the pacemaker, triggering a fatal heart attack.

More than a decade on, the security of networked medical devices is a serious concern for many reasons. Concerns are growing as devices are engineered to gather and report increasing amounts of data, most of it collected and transmitted using widely available, off-the-shelf software. (Source: EE Times)

As Emmett points out, the real worries aren’t about attacks on individuals like Vice President Cheney or the VP on Homeland. They’re around data mining, and using the information for financial gain.

Hacked data can reveal commercially valuable information, such as performance data on competitors’ products. Such data can be used to exploit weaknesses in a rival’s marketing or used to modify the company’s own offerings.

Networked devices provide feedback on a wide range of patient data such as blood pressure, respiration, blood enzyme levels, and other health conditions. Insurers that issue individual life insurance policies often purchase this information — repackaged by third parties to be of apparently legitimate origin — to assess clients for insurability and to set premiums.

She also notes that fitness devices, like Fitbits, also produce large quantities of biometric information.

The FDA has released some guidance on cybersecurity for medical devices, and legislation has been introduced that would “codify protections for medical device data.”

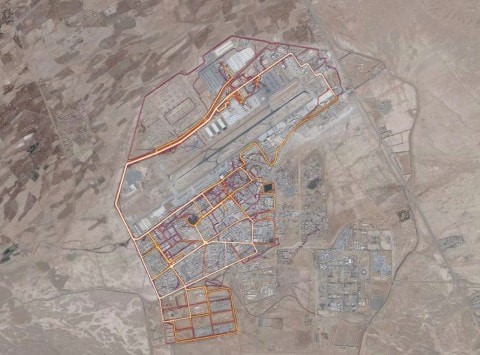

Emmett’s post was particularly timely given the recent news that fitness device data, from devices worn by U.S. soldiers, could potentially be used to identify their locations. Heat maps developed by Strava, a GPS tracking company, aren’t real-time depictions, but could help enemies figure out sensitive information. When the heat maps show affluent regions in the United States and Europe, where so many millions of people wear fitness trackers, the picture is pretty dense. In poor regions in the Mideast and Africa, where fitness consumers are few and far between, what shows up on the maps are the areas where Fitbit-wearing soldiers congregate.

An Australian student was the first to notice that a heat map of Syria showed where soldiers congregated. A journalist found information that likely gives away the location of a CIA base in Somalia. A Twitter use claims that “he had located a Patriot missile system site in Yemen.” (The heat map shown here is of Kandahar Air Force Base.)

The U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State said on Monday it is revising its guidelines on the use of all wireless and technological devices on military facilities as a result of the revelations.

“The rapid development of new and innovative information technologies enhances the quality of our lives but also poses potential challenges to operational security and force protection,” said the statement, which was issued in response to questions from The Washington Post.

“The Coalition is in the process of implementing refined guidance on privacy settings for wireless technologies and applications, and such technologies are forbidden at certain Coalition sites and during certain activities,” it added. (Source: Washington Post)

Technology that both “enhances the quality of our lives” while at the same time posing “potential challenges” pretty much sums up the Internet of Things when it comes to the consumer end of the product spectrum. There may not be someone out there who’s going to hack someone’s pacemaker and throw them into cardiac arrest, but a lot of the security challenges that have been addressed in the industrial IoT have yet to be seriously taken when it comes to consumer devices, including some life and death ones.